The Dodd Room

England's oldest gaol, built in 1333 from the stone of the Corbridge Roman site.

Hexham Old Gaol is the earliest recorded purpose-built prison in England. It was ordered in July 1330 by William Melton, Archbishop of York, who sent a letter to Thomas Fox, Receiver of Hexham, demanding a gaol where his prisoners could be securely guarded.

The archbishop ruled over Hexhamshire, and the construction of the Gaol was a symbol of his great wealth and power. Any fines from offences committed in the area were paid to the archbishop, so it made sense to open his own gaol as a way of making money and controlling the people who lived and worked on his land.

Prisons up until this point had normally been part of castle buildings or were in buildings that had been adapted from their original use.

The Gaol was completed in January 1333, made from the stone of Corbridge Roman Fort, located just three miles away.

It was fitted with torture and punishment devices such as manacles and fetters. Prisoners, depending on their status and the seriousness of their crimes, were held on three floors. The dungeon was a miserable place for the poorest and most hardened of criminals. It was dirty, smelly and overcrowded. In contrast, the first floor was a much more pleasant experience for wealthy prisoners.

The Gaolers lodgings were on the top floor. The first Gaoler of the prison was John de Cawood, who was employed in 1332. He was paid 2d and his job was to oversee the prisoners. When they arrived, he would search them, put them in chains and escort them to their living quarters.

Gaolers were expected to earn more money by charging the prisoners additional fees:

It's likely that wealthier prisoners bribed the Gaoler for extra privileges, such as, better food, better bedding, access to the Market Place to beg for alms, and to be able to attend church.

The Gaoler managed the prisoners' work. Prisoners were expected to contribute to the running of the Gaol, carrying out tasks such as cleaning toilets and collecting urine for selling to the local tanning industry.

The Gaolers were expected to maintain law and order but that was a very difficult job when prisoners were allowed to gamble, often getting into arguments and attacking each other, and women and children were not segregated from men.

Prisoners were not regularly cleaning themselves or their clothes, so lice was a major problem. Typhus, also commonly known as 'gaol-fever', was a bacterial infection spread by fleas and lice, and was rife throughout the Gaol. It caused rashes, fevers and chills. If left untreated it was fatal. Prisoners would fall into a coma and die.

The Gaol was infected several times by the plague, a disease spread by the permanent presence of rats.

The Gaol was designed as a pre-trial prison where the accused were held while they awaited trial at the nearby Moot Hall. Prisoners were meant to be taken to court and tried at least four times a year, but this didn't always happen, and prisoners could be held in the Gaol for many years.

When a trial did take place, prisoners were shackled for the walk from the Gaol to the Moot Hall. They formed a procession with the Gaoler and his staff. Prisoners were chained to a bar until it was their turn to be tried. The shackled were removed while they answered the charges against them.

Juries were made up of the local townspeople who very likely knew all about the alleged crime and the accused. Many trials lasted less than half an hour.

Prisoners could be acquitted (found not guilty), found guilty and sentenced to a shaming punishment or found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging, which would be carried out immediately in the Market Place.

Hangings were rare because the Church did not agree with the death penalty except for very serious crimes.

Prisoners who were found not guilty were free to go once they had paid outstanding fees for food, drink, clothes and bedding. Around 80% of prisoners were found not guilty.

Those who were found guilty and sentenced to a shaming punishment could be dealt with in several ways.

Branding and amputations were carried out immediately after the verdict and were for prisoners who had committed crimes like theft, and in some cases, murder. Criminals would often have hands, fingers and ears cut off. This would affect how they were treated, spoken to and whether they could get a job in the future.

Those who had committed less serious crimes would be subjected to shaming through the stocks, the pillory, the ducking stool or the whipping post. The stocks, pillory and whipping post were in Hexham's Market Place, and the ducking stool was on Tyne Green by the River Tyne.

The local townspeople would often make things worse by throwing objects, shouting or hitting the person while they were serving their punishment.

Punishment also came in the form of being sent back to prison and fines which would be paid to the archbishop.

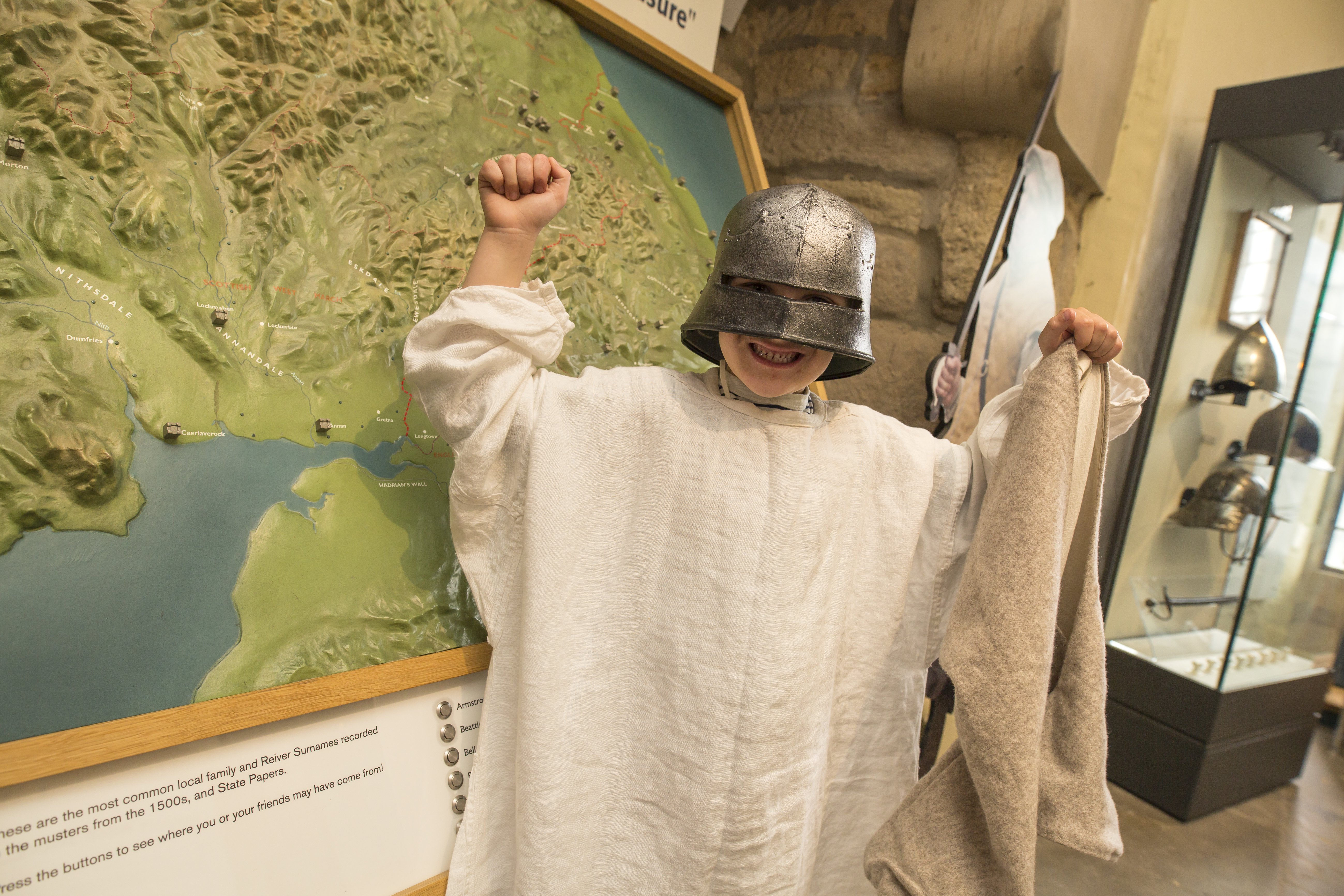

The Gaol became home to numerous Border Reivers between the 14th and late 17th centuries. Border Reivers were infamous criminal groups operating on the lawless border between England and Scotland where murder, stealing, arson, kidnapping and extortion were part of everyday life.

Reivers were made up of English and Scottish families and came from every walk of life. Scottish Reivers would attack other Scots and English Reivers would attack other English people. Often, the Scottish and English Reivers would join forces - anyone outside of the immediate family group was a target. Common family names for the Border Reivers were Charlton, Dodds, Milburn, Armstrong and Robson.

Attacks were carefully planned and ranged from large groups of armed men travelling distances over days to small raids on local farms.

The English and Scottish governments had tried to put a stop to the unrest on the border but had largely failed. It was not until the union of England and Scotland through the crowning of James I in 1603 who ruled over the new kingdom of Great Britain, that order began to be restored.

Many people who had taken part in the Hexham riot on 9 March 1761 found themselves locked up in the Gaol. The riot was the last of several demonstrations in Northumberland against the 1757 Militia Act.

Men between the ages of 18 and 50 were put on a list for military service and names were drawn from this list. This was not popular, as it meant that the main breadwinner or all the men in one family could be selected. Servicemen weren't paid enough to cover this loss of income and families feared they would be driven into poverty. Men would be taken away from their families and livelihoods and expected to serve anywhere in the country for up to three years.

Over 50 people died and many more were injured in Hexham Market Place when the Riot Act was read and the militia opened fire after the crowd refused to disperse, and fighting broke out.

The Gaol was in use as a prison until the 1820s. It then became a bank and a solicitor, L.C. Lockhart owned by the Lockhart family. The family made several alterations to the building, including the installation of a staircase and electric lighting. A flushing toilet was added, and the walls were plastered with medieval designs.

Today, the museum tells the story of the Gaol's rich history and explores what life was like for the local townspeople of Hexham.

You can take a trip in the glass lift to see the dungeon, learn about medieval crime and punishment, and the lawless Border Reivers who were imprisoned in the Gaol.

Hear gruesome stories about the Gaol's colourful characters from an expert tour guide, and have a go in the stocks if you dare.