Our collections, galleries, & research

Managed by North East Museums on behalf of Newcastle University

In 1793, the Literary and Philosophical Society of Newcastle upon Tyne – affectionately known as the Lit and Phil – opened its doors as a place for lectures, debates, and the exchange of ideas. From the start, curiosity sparked collecting. In 1800, the Society acquired its first unusual specimen: a wombat! Over the years, these early collections grew to include animals, fossils, minerals, and other objects that would lay the foundation for a public museum.

By 1823, the Society purchased the natural history collection of Marmaduke Turnstall, a wealthy enthusiast with an impressive array of animals, insects, and dried plants. Soon the Society ran out of room. In 1825, they moved to Westgate Road, where the Lit and Phil still stands today.

The collections became too large and diverse to remain together, so the Society decided to separate the library from the natural history specimens. This led to the creation of the Natural History Society of Northumbria, Durham, and Newcastle upon Tyne in 1829. That same year, the Society gave its first public natural history lecture on a newly discovered species of swan. The bird was later named Bewick’s Swan, in memory of the celebrated local naturalist Thomas Bewick.

By 1831, the Society published its first journal, Transactions, sharing discoveries with scholars and enthusiasts alike. Following a fundraising campaign, the collection moved to new premises behind the Lit and Phil in 1834, becoming the Newcastle Museum. Remarkably, this was the first museum in the region to welcome the public for free, initially opening just one evening a month.

John Hancock, Secretary of the Society, was a driving force behind the museum’s growth. Born in 1808, Hancock had been fascinated by nature from a young age—collecting plants, insects, and birds, and even training falcons on the Town Moor. His skills as a taxidermist ensured the museum’s collections were both scientifically accurate and beautifully displayed.

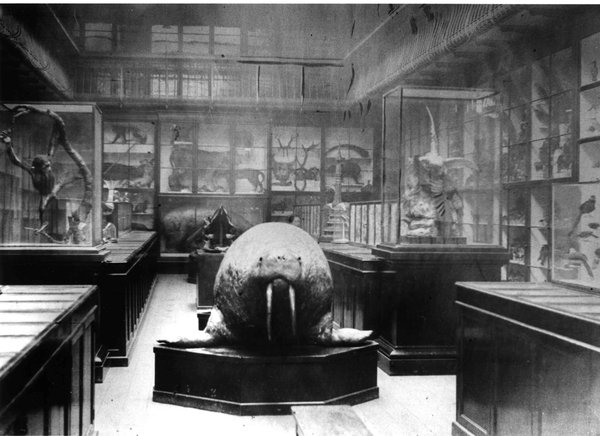

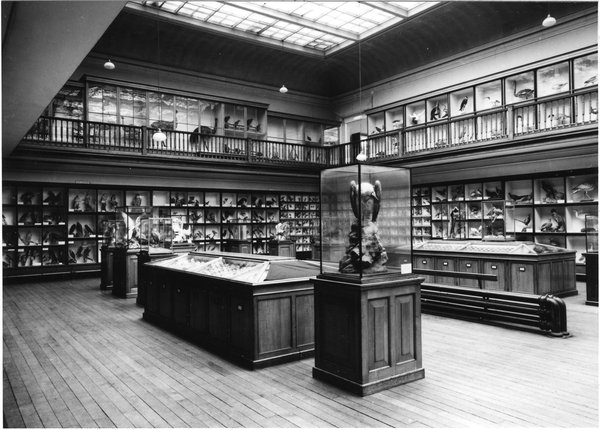

The museum’s growing collection soon outgrew its home. John Hancock saw an opportunity in a plot of land at Barras Bridge, conveniently opposite his house. With his brother Albany – a renowned naturalist – Hancock planned an ambitious new museum. After four years of construction, the New Museum of Natural History opened in 1884, celebrated with a lavish ceremony attended by the Prince and Princess of Wales.

Hancock’s bird collection, and included iconic pieces such as his sculpture Struggle with the Quarry, now displayed in the Natural Northumbria Gallery. After John Hancock’s death in 1890, the museum was renamed the Hancock Museum in tribute to both John and Albany.

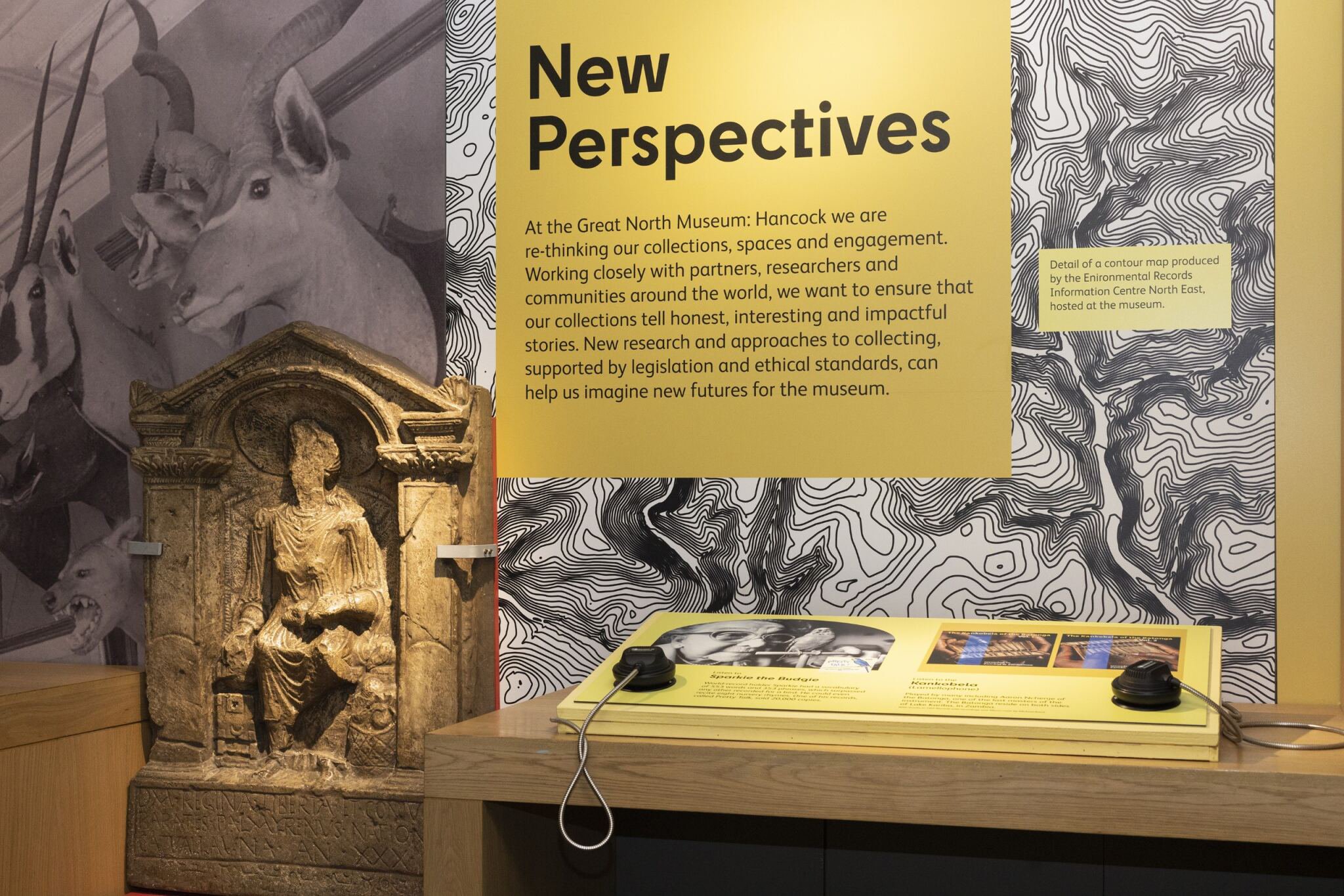

By the 1960s, the Barras Bridge building had served Newcastle for almost 80 years, but maintenance costs and the demands of modern exhibitions meant it needed a major update. King’s College (now Newcastle University) took over management, integrating collections from the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne (founded 1813) and the Shefton Collection of Greek and Etruscan artefacts, which began with a modest grant of £25 in 1956 and grew to nearly 1,000 objects under Professor Brian Shefton.

In 2006, the museum closed for a £26 million redevelopment to create a museum fit for the 21st century. When it reopened in 2009 as the Great North Museum: Hancock, it brought together natural history, archaeology, and cultural treasures under one roof, while celebrating the legacy of its founders.

On the second floor, the museum’s Library is a hidden gem. Visitors can browse thousands of books and journals from the Natural History Society of Northumbria, the Society of Antiquaries, and Newcastle University’s Cowen Library. From rare sixteenth-century volumes to modern children’s books, the Library reflects the museum’s commitment to research, learning, and curiosity. Best of all, it’s completely free to visit—no membership required!

The Environmental Records Information Centre for the North East is also based at the museum. ERIC works with wildlife recording groups and individuals to collate environmental data which is used to inform nature conservation.