Our collections & galleries

Managed by North East Museums on behalf of North Tyneside Council

Segedunum, the Roman fort at Wallsend, marks the eastern end of Hadrian’s Wall. For almost 300 years, the Wall formed the north-west frontier of the Roman empire.It’s from its Roman past that Wallsend takes its name, but the town is equally famous as a world leader in both coal mining and shipbuilding. Built around AD125, Segedunum was part of an extension to Hadrian’s Wall, built three or four years after the main construction of the Wall.

The fort was built on a plateau overlooking the north bank of the river Tyne, at the point where it turns to run to the Coast at South Shields. The site was perhaps chosen to command views eastwards down the river towards South Shields, and upriver towards Newcastle. 'Segedunum’ means ‘strong fort’ which was recorded in a Roman document, the Notitia Dignitatum, written in the late fourth century AD, around the time of the end of Roman Britain.

Hadrian’s Wall ran for 80 Roman miles (113km /73 modern miles) from Bowness-in-Solway to Wallsend. It was a formidable obstacle built to mark the north-west frontier of the Roman empire and to keep away invaders, but it’s size and scale was also designed to impress upon enemies the might and power of the empire. Three Centuries of Upheaval Inside the Fort WallsWallsend Colliery

A frontier was already in place before the Wall was built which consisted of a series of forts connected by a road. Hadrian’s Wall was placed slightly to the north of this and was mostly constructed in stone. Originally, there was a 42km turf section at the western end, but this was also later replaced by stone. , except where crags or rivers made this unnecessary. In some parts there were branch entanglements (like barbed wire) between the fort and ditch.

Placed at one-mile intervals there were gates protected by a small guard post called a milecastle. Between each pair of milecastles were two towers or turrets which created observation points at every third of a mile. The stone wall was approximately 4.6m (15 feet) high and 10 Roman feet (3 m) wide (although the height and width did vary along the Wall), so it was wide enough for a walkway and a parapet wall on the top.

Before the original design was completed there was a major change in plan. It was decided to add forts to the Wall itself, approximately 11km apart. Behind the Wall a massive earthwork was built (now called the Vallum), consisting of a massive flat-bottomed ditch flanked by two huge mounds. This marked Originally, the Wall was going to finish at ‘Hadrian’s Bridge’ (Pons Aelius), a grand bridge across the River Tyne. Newcastle and Gateshead did not exist at this point – even the fort at Newcastle was built many years later. and there was no vallum. It is thought that the Wall took at least six years to build, with approximately 15,000 soldiers involved in the project.

Before the Romans built Segedunum Roman Fort, the area was farmland, lying within the territories of the Brigantes tribe - a large tribe whose lands stretched from Yorkshire up to Northumberland. Archaeologists have found evidence of ploughing and the hand-digging of furrows in preparation for the sowing of crops. The farmstead, which would have been made up of round- houses was probably to the north of the later fort.

Before the Romans arrived here, people lived in farmsteads about a 15 minute (1km) walk apart. Some were made up of one or two main, larger roundhouses and a number of smaller round-houses, surrounded by impressive earth banks and ditches. Fields for crops and pasture for animals would lie outside the ditches. A farmstead like this could be a home for 15 – 30 people and could take up as much space as an entire Roman fort.

>span class="TextRun SCXW92136682 BCX0" data-redactor-span="true">cattle and other animals may have been kept on the ground floor, while people lived on a timber floor above them. >span class="NormalTextRun SCXW92136682 BCX0" data-redactor-span="true">a huge impact on natural resources. Evidence suggests that the land built beneath the fort at Wallsend had been prepared for crops just before the fort was built, suggesting that the local people were not expecting a fort to be built there. The Romans confiscated the land, and the farmers had to move elsewhere.

1) When first built the barracks were made of timber, and only the central range of buildings were of stone.

2) Within 50 years the timber buildings had been knocked down and replaced by ones made in stone, and a stone hospital was built. This was soon reduced in size to allow better access for vehicles through the minor west gate.

3) In the early part of the third century 60-(or-so)-year-old barracks were once more demolished and replaced by a new style of back-to-back barracks. The hospital disappeared entirely, and small timber buildings fill previously open spaces within the fort.

4) In the fourth century the minor west gates seems to have become a market-place. Use of the site probably ended in the late fourth century, about the year 380.

The completed Wall had only been standing for about 10 years when Hadrian died, and 4 years later the next Emperor, Antoninus Pius, started work on a new frontier much further north in Scotland, called the Antonine Wall. Hadrian’s Wall was neglected, and it is unclear whether Segedunum was left empty or had a reduced garrison at this time. Twenty years later, the Antonine Wall was abandoned, and Hadrian’s Wall became the frontier again. Over the years, there were changes to the milecastles and major repairs were carried out. At Segedunum, there is evidence for the Wall falling down on at least three occasions because it had not been maintained properly.

Without anyone to maintain it, parts of the Wall gradually collapsed over the years. During the late Anglo-Saxon period, when building with stone became popular again, the fort became a convenient quarry for stone already cut to size. The fort site remained visible for many years and is why the medieval villages of Wallsend and Walker include 'wall' in their , people removed even more stones, and it disappeared – although the dip caused by the ditch were used as duck-ponds in local farms up until the 1930s.

In the mid-18th century this part of Wallsend belonged to the Dean and Chapter of Durham, who in 1777 leased the mineral rights to William Chapman. His early attempts were disastrous: one trial shaft vanished into quicksand, and work on a second (later the A pit) ended when his loan was recalled in 1780. Creditor William Russell then took over. In 1781 fortunes improved when miners struck the High Main seam at 666 feet (around 2 m). A second shaft, the B pit, was sunk soon after just 70 m north, beside the fort’s north-west corner—its remains still visible today.

By the early 1800s Wallsend Colliery had six interconnected shafts and produced what was considered the world’s finest household coal. Waggon-ways carried it to collier ships on the Tyne beside the fort, bound mainly for London. Much of the mine’s success came from its skilled managers, especially John Buddle Jr., who took charge in 1803 and became the era’s leading coal-mining expert, pioneering major safety improvements.

Wallsend’s fame drew notable visitors, including Grand Duke Nicholas of Russia in 1816. After peering into one shaft and calling it “the mouth of hell,” he refused to descend. In 1820–21 the deeper Bensham seam was reached at 870 feet (around 265 m). By 1831 the High Main seam was exhausted and B pit served mainly as an air shaft. Disaster struck on 18 June 1835. A huge underground explosion around 2 p.m. killed all but four men and one boy out of 107 workers—including 32 children—and ten horses. Seventeen boys and a deputy overman who tried to lead them to safety were later found; the G pit shaft they aimed for had been blocked by the blast.

By the mid-19th century flooding closed the mine. It reopened in the 1890s with workings half a mile north of the fort. By century’s end the A pit had disappeared, and the B pit continued as an air shaft for Wallsend (later Rising Sun) Colliery until its closure in 1969.

By the mid-19th century coal mining in Wallsend was fading, but new industries were rising. Chemical works grew nearby, while the site of the Roman fort shifted decisively toward shipbuilding. Iron shipbuilding arrived on the Tyne in the 1840s, and in 1863 Schlesinger, Davies & Co. opened a major yard beside the fort. It thrived for two decades but never recovered from the 1884 recession and closed in 1893.

A second yard opened in 1873 just to the east. After early struggles, it flourished under manager Charles Sheriton Swan as C. S. Swan & Co. When Swan was tragically killed in 1879, his wife brought in George Burton Hunter as partner and Managing Director. The firm grew rapidly, becoming a limited company in 1895 and expanding to include the former Schlesinger site in 1897.

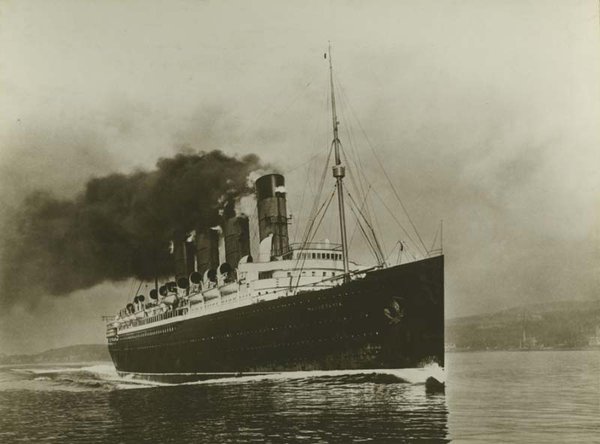

As heavy industry boomed, demand for worker housing surged. In the 1880s the fort site was sold to a builder and disappeared beneath new streets and terraces for nearly a century. In 1903 C. S. Swan & Hunter Ltd merged with J. Wigham Richardson of Low Walker to bid for the construction of the Mauretania, the Tyne’s most famous liner. The partnership became permanent, forming Swan, Hunter & Wigham Richardson Ltd. Swan Hunter went on to become one of the world’s leading shipbuilders. Over its 130-year history it produced more than 1,600 vessels—from tankers and cargo liners to destroyers, submarines, icebreakers and floating docks—exported across the globe.